- Home

- Nevo Zisin

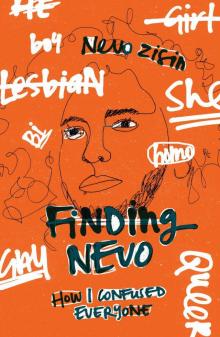

Finding Nevo

Finding Nevo Read online

Table of Contents

Cover

Blurb

Black Dog Books Logo

Chapter 1: Pretty (Pained) in Pink

Chapter 2: The Only Constant Is Change

Chapter 3: Misogyny For Beginners

Chapter 4: Wrongs of Passage

Chapter 5: Queerings

Chapter 6: My Mother Doesn’t Know My Name

Chapter 7: The Path To Passing

Chapter 8: School Is A Battlefield

Chapter 9: Testing Testosterone

Chapter 10: I Am Not A Box

Chapter 11: Here, Queer and Jewish

Chapter 12: A Path To Unlearning

Chapter 13: The Future is Femme

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Glossary

Resources

Suggested Reading

Copyright

Dedication

Meet Nevo: girl, boy, he, she, him, her, they, them, daughter,

son, teacher, student, friend, gay, bi, lesbian, trans, homo,

Jew, dyke, masculine, feminine, androgynous, queer.

Nevo was not born in the wrong body. Nevo just wants

everyone to catch up with all that Nevo is.

Personal, political and passionate, Finding Nevo is an

autobiography about gender and everything that comes with it.

“A gorgeous coming of age story about one person’s journey

to discover themselves. Zisin is a compelling storyteller with

a delightful and exciting new voice.” Clementine Ford

Nevo, dressed as a pirate for Purim, approximately four years old (2000)

Chapter 1: Pretty (Pained) in Pink

There’s something quite ironic about writing a life story at my age. I am only twenty after all.

My story begins before I was born.

My mother had a life of travelling and fun interspersed with studying and working as a teacher. But at a certain age, she said, she felt that her biological clock was ringing, and she decided to settle down and take things slower (though most people who know her would say slowing down is not in my mother’s vocabulary). At thirty, she met my father and they married. My dad already had three children from a previous marriage but it was important to my mum to have a child. They had some complications while trying to conceive so had to go through IVF treatment. In my mum’s words, “Each menstruation brought grief and mourning.” Eventually, on the third try, she conceived.

My mum was desperate to have a daughter. She knew due to the fertility issues they had, she would likely have only one child. She prayed for a girl. When asking people whether they would like their baby to be a boy or a girl the usual answer is, “I don’t mind as long as it’s healthy,” but that was not my mum’s response. She had picked out only girls’ names and was certain of the fact. I often joke with her that her desperation to have a daughter resulted in my trans identity.

Apparently, the moment I was born, she anxiously asked her mother, “Well, what is it?” To which my grandmother replied, “It’s a boy!” My mum was horrified, but the doctor quickly interjected and explained I was indeed a girl. My mum was relieved. I wish I could have spoken on behalf of myself then and there; I could have avoided a lot of issues down the track.

I was born into a Jewish family, consisting of a mother (thirty-eight), father (forty-two), half-brother (thirteen), other half-brother (twelve) and half-sister (ten). My dad is Israeli and my mum was born in Australia. Her parents were Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe who immigrated to Australia during the war.

I was a confident and outspoken child. I would put on performances for my parents and their friends. A friend of my mother’s once told her I would either end up as prime minister of Australia, or in jail – the jury’s still out on that one.

It is commonly thought that children are aware of their own gender from about the age of three. At age four I was set on the fact I was a boy. I refused to go to the girl’s section at department stores and would only wear clothing designated for boys. Whenever people referred to me as a girl, I would quickly correct them. This led to a few funny instances of strangers asking my gender and my father and me arguing about it. Once, when accused of being a drama queen, my retort was, “I’m a drama king.”

My mum was upset about all of this, as she had desperately wanted a girl, and to her that involved a certain level of femininity. She wished I would wear dresses and she hated the clothing I insisted on wearing. I liked anything with dragons, skulls or fire. Mum tried to set boundaries as to how masculine I could be. She didn’t allow me to cut my hair too short and when she left the room I would instruct the hairdresser to keep cutting. She was saddened by my choices to wear suits in preference to a dress. My dad thought it was entertaining and encouraged me to wear whatever I wanted.

People were not always comfortable with my free expression. At the age of about five, a family friend invited me to her mermaid-themed birthday party. I was not interested in wearing a blue bikini like the rest of the girls; I went as a pirate. I also remember going to synagogue occasionally with my grandma and wearing a suit and kippah (the traditional Jewish head covering – historically worn by boys) and the rabbi was very uncomfortable with it.

At one stage, my mum was coming home from a holiday and I went to the airport wearing a dress. I knew that despite how miserable it would make me, she would be incredibly happy and surprised; and she was. Even at a very young age I learned to compromise my own happiness to fulfil my parents’ expectations. Later in life when I tried to conform to femininity to fit in, I could see how happy it made my mother, despite the fact that I was lying to myself.

When I was about seven or eight, my mum and I used to go to a family friend’s swimming pool. I wore board shorts and swam shirtless and spent a lot of time constructing games to play by myself. One day, our friend decided I was too old to swim with my shirt off, and my mum told me I would have to start wearing a shirt. I was devastated. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t continue to be topless like my male friends, or brothers, or my dad. They were older than me but they were still allowed to expose their chests. My mum explained I was growing breasts, something I hadn’t been aware of until that moment. I was suddenly acutely aware of my chest in a way I hadn’t been before and felt the need to hide it. I felt embarrassed, ashamed and self-conscious. I wore a shirt from then on.

I had a lot of struggles in my early childhood. I began my education at a private Jewish school where my mother was a teacher at the secondary campus. Boys dominated my year level (as is usually the case in broader society), and I found myself drawn to hanging out with them over the girls. I remember some boys were quite aggressive towards me. I was bullied a lot for being a “tomboy” and also for my weight. I was a chubby little kid and the other kids at school often reminded me of this. These kids already had such ingrained fatphobia and misogyny. In order to fit in, I bullied other kids and that led to a lot of social issues and total loneliness. I wasn’t sure how to interact with others. I really struggled to make friends and I spent a lot of time on my own.

One time, my mum and dad went on a holiday for six weeks and left me with my grandma. My mum sent messages to the parents of the kids in my class, explaining the situation and encouraging them to make as many play dates with me as they could while my parents were away. Not one person arranged a thing. I remember the effect this had on me and I still feel the pain. I can’t imagine I would have been the nicest person to hang out with anyway because I was so angry all the time, but I didn’t know how else to be. I wasn’t receiving the support I needed. I saw a psychologist because my parents were concerned about my social issues and the fact that I was presenting as male, but I don’t remember gettin

g comfort or support from it, rather feeling like there was something wrong with me. I felt incredibly lonely most of my childhood.

All of the difficulties I was experiencing were magnified when I got older and moved campuses. The new campus was huge. I was lost and afraid and alone – miserable, with no real friends. A lot of the boys told me I couldn’t play with them any more and there was also the presence of older, more intimidating kids. The girls in the years above gushed over how cute the girls in my year were, but they never spoke to me and I felt invisible. I spent most of my lunchtimes walking around the oval on my own or pretending I was sick so I could visit the school nurse. I went there almost every day in the hope I would see my mum and be able to cry to her.

The one time I felt accepted was when a boy in my class and I were playing with the desks and one landed directly on my toe. I ended up in a wheelchair for the rest of the afternoon and everyone was nice to me. For that afternoon, it felt like things could get better. My class made me a card and when I came back to school, I was actually happy to be there.

It didn’t last long.

By the end of Year Three, I was truly miserable. The transition to the larger campus had been too hard. Like most kids, it was difficult for me to understand what I wanted and needed. I knew on some level I needed to move schools, but I didn’t see that it was a realistic option. While I was trying to figure out how to approach the subject with my mum, she was struggling with how to approach it with me. The school had retrenched a number of teachers, my mother included. This meant I’d have to move schools because we would no longer be receiving the discounted school fees and couldn’t afford to pay them at full cost. When my mum told me, I cried, because I couldn’t have been happier.

I was to have a trial day at my new school, and Mum set up a play date beforehand with Leila, a girl the same age as me, who she knew through friends. I had never gotten along well with girls but I was desperate to have a new friend, or really, any friend at all. Leila was loud and extroverted. I wasn’t sure exactly how to interact with her, but I tried my hardest to be nice. We played computer games and chatted. Years later I found out that the whole time she thought I was a boy and had a bit of a crush on me. I look back on this day as marking the beginning of a huge change in the direction of my life.

I had my trial day during the last term of the year. I was nervous. I entered the unfamiliar territory of a public school around the corner from my house. I had little experience of interacting with anyone outside of the very insular Jewish community and had no idea what to expect. All I knew was I was terrified – terrified of the unknown, of being alone and of being bullied.

The class I joined were decorating rocks. I kept to myself and engaged in the activity. Soon Leila grabbed my arm and pulled me over to her table with her friends. She introduced me to each of them, though the one that particularly stood out to me was Shannon. A tiny, energetic pocket rocket, Shannon immediately started talking to me and asking me questions. This was a pivotal moment for me and I will never forget it. No one had ever been excited to be my friend. I later met Siobhan and the four of us – Leila, Siobhan, Shannon and I – formed a friendship group that would become the main support network in my life. Years later it remains to be that.

In Year Four, I officially moved to my new school. I was excited and anxious, ready to leave behind my past and the people that had treated me badly. I wanted to start anew, with newfound friends. However, it wasn’t as easy to transcend my old life as I had hoped. I still had a lot of misplaced anger and aggression and didn’t know how to navigate it or what to do with it. I continued to interact with others in antagonistic ways and isolated myself from the social groups at school. Eventually, Shannon pulled me aside and said, “Listen, I’ve spent a long time earning my reputation here and you’re ruining it. If you want to continue to be my friend you’re going to have to get your act together.” That was one of the most important conversations of my life. I realised I had people who cared about me, and the way I behaved. What Shannon said made me feel loved, and this helped me take apart the anger I had been holding onto for so long.

Although it still took time, I worked through a lot of that anger and identified that if I wanted to maintain the most important and healthiest relationships I had ever had, I needed to behave more respectfully. For the first time this change was possible, because I felt I had people who supported me.

During this period, I was desperately afraid of not fitting in with the other girls. They invited me to a surprise party they were organising for another friend. I decided that my best bet for fitting in would be to present as femininely as I could. I wore heels, a dress and make-up. I showed up to the party eager to display what I was capable of disguising myself as. Then I realised no one else was dressed like I was and I felt awkward the entire night. It took a while experimenting with different looks and styles to realise the girls actually didn’t care what I looked like, they just cared about me. The more I tried to conform, the less I fitted in. The only thing the girls had in common was that they were each unique, powerful and strong, and they loved each other. When I stopped trying so hard to be something I wasn’t and allowed myself to be who I was, it was a relief. The only way I could last in this group was by embracing myself. So I did.

Though I know now there was a lot I didn’t understand at that time about my identity, at this new school I began the process of understanding who I was. After leaving my previous school, which left me quite broken, I couldn’t see what my redeeming qualities were. I had a significant amount of self-loathing. The girls took me in and taught me what was great about me.

It was radical for me to be part of a group of powerful girls. Up until this point, I had mostly spent time with boys and I had developed a strong sense of internalised misogyny. I saw the feminine parts of myself as lesser. To meet a group of confident girls who taught me I could be myself, and be proud, was revolutionary. This was a period in my life where I strongly identified as female, and a very proud one at that.

This was a time when we all thrived. Looking back now, I can’t remember actually sitting in classes. I can only remember the adventures and conversations and things we learned together. We would sit outside the classrooms referred to as the “portables”, gossiping on the picnic tables, watching people pass by. For a few years, I truly felt on top of the world. In my mind at least, we were the popular kids. Our friendship group was exclusive and secured. We set a trend in the school, where we wore our school dresses with the school pants underneath. It looked silly, but we loved it and it soon spread around the school. It was a big deal for me to be able to wear a dress with pants underneath and not feel out of place. As a child I would only ever wear dresses with shorts under, so for this to become the norm in the school was quite significant.

This too was the place where I had my first boyfriend. I was in Year Five, in “love” and ready to settle into the kind of glamorous and glorified relationship that had been spewed to me in film after television show after melancholy heartbreak song. I was ready. The boy was in the year above me and I told him I had a crush on him. The relationship lasted about a month, as most true loves in Year Five do, and we went our separate ways.

Nevo with their father, approximately four years old (2000)

Chapter 2: The Only Constant Is Change

So much in my life has changed, it is the one thing I can rely on. Things will always change. It is important to explain different parts of my childhood in order to understand how I was shaped as a person, and how I evolved. So the following parts may seem disjointed, but stick with me, because it will help you understand who I am as a person.

Growing up with much older siblings was difficult. They already had established relationships and I felt like I was an add-on. I was never really sure of what my place was within the family. My siblings were not always nice to me. Whenever we would get together for a Friday night dinner it seemed they had a competition to see who could make me cry first. I

left the table many times in tears. I felt ganged-up on throughout my childhood. I think in part this may have been because of the significant age gap.

However, I also think there was an aspect of resentment that my siblings held against me. When they were born, my father was not as established in his career and had to work much harder to provide for them. I think they felt I had a much more privileged upbringing than what they experienced. They all went to public schools and saw my attendance at a private Jewish school as a sign of me being spoiled. From a young age, I tried to be aware of the opportunities I was afforded that they weren’t, but I was often spoken over, patronised and taught that until I had more life experiences, my opinion was not valid. I felt like anything I said to them was wrong. They didn’t care much about my presentation as a boy, and never really commented, but I didn’t feel supported by them. I recall telling my brother about the bullying I was experiencing and how miserable I was, and his response was, “There are kids dying in Africa, you have no idea how good you have it.” Because I wasn’t particularly close with my siblings, I learned to rely on and enjoy my own company. I had an active imagination and escaped into my own created realities.

One of my biggest secrets was that I loved to play with Barbies. I was embarrassed because they were so girly. I escaped from some of the difficulties in my life by creating my own intricate world of invented characters. It wasn’t a reality without its own challenges. I had divorced couples, cheating spouses; I even had a brother and sister that had escaped genocide.

A few times, my dog got into my collection and ripped apart some of my dolls. Once I had appropriately mourned their loss, I developed storylines around how they had died. I was very self-conscious about people watching me play. It was a deeply personal activity and I needed to do it alone. Although this world was nowhere near perfect, it was entirely mine and I felt important.

Finding Nevo

Finding Nevo