- Home

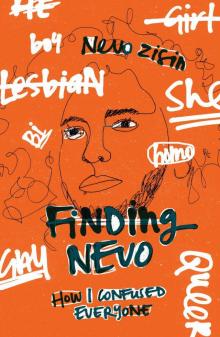

- Nevo Zisin

Finding Nevo Page 2

Finding Nevo Read online

Page 2

I escaped into the narratives of my dolls because it was easier to face than what was going on in my real world. Although social issues at my new school were beginning to resolve, I was struggling at home. My parents were fighting a lot and I wasn’t sure how to deal with it. I would see my mum cry and try to comfort her. I tended to take her side. I learned from a young age that crying is a sign of weakness. So when my parents fought and I saw one crying, I resolved that this was the place my support was most needed. Over time, I’ve learned that tears can be a sign of strength and I know now how strong my mother is. But I remember as a child trying to hide my tears. Overflowing with emotion and anger until tears poured out, incriminating me, labelling me as some sort of vulnerable weakling. I remember countless times, running into my room, trying to hide the shame.

I have also learned that a lack of tears does not necessarily mean a lack of emotion, and that just because I never saw my dad cry doesn’t mean he wasn’t feeling the same pain as my mum. I’ve had to think about this a lot because testosterone has now left me far less capable of crying. I love crying, but I can’t as often or as much as I feel the need to.

Another important escape for me was the youth movement I attended. Youth movements are a big part of the Jewish community. There are quite a few, all with varying ideologies and relationships to religion. It’s hard to explain what these groups are like to people who have never experienced them for themselves, but a large part is the environment they create in which children have the space to explore issues in the world critically, and actually be listened to. When I was young, my mum sent me to Habonim Dror (Habo). It was the same youth movement she had attended and been a leader in. I was eight years old and beyond excited for my first meeting, even though I didn’t know anyone and wasn’t sure what to expect. I saw it as an opportunity to start fresh and make friends. A lot of the kids knew each other from school and I wasn’t sure how to fit in. I felt out of it for most of my time in the movement. I was different from other kids. I wasn’t picked on, but I was mostly ignored. I preferred to be invisible than bullied. I spent a lot of time with the leaders.

I had never interacted with people in their twenties before. These youth leaders were volunteering their time and energy to be educators, and also to provide support and respect for children who wanted to feel heard. Suddenly my opinions were valued and I wasn’t told that I didn’t know what I was talking about because I was too young.

I owe a lot to this unbelievable place. Every week, I knew there was a safe space waiting for me and people who wanted to see me. I learned how to interpret the world around me and why it’s important to be an activist and educator. My motivation to be a role model can be traced back to my early days in this movement. It made me a better person and I am so lucky for that. When everything else changed around me, Habo was the constant in my life.

Another large part of my childhood was music. I come from a musical family: my sister plays piano and drums, my brother is a rapper and my eldest brother is a pianist. I remember him trying to teach me piano and telling me I had to practise every day. I went to my mum and said, “What does he think? I can’t practise piano every single day! I have a life!” I was six.

When I was about seven years old, my family went to my uncle’s house for dinner. I found an old, rusted trumpet and picked it up to see if I could make a sound. An overwhelmingly loud and obnoxious noise filled the air. I loved it. I begged my mum to let me have trumpet lessons at school. She refused. She tried to convince me it would be more practical to learn guitar or something that I could take with me on Habo camps, something to sing with around the camp fire. But I didn’t want that. I got such a rush from playing the trumpet that I wanted to see what I could do with it.

Eventually, she gave in and let me have a trial lesson. I walked the long corridors of my school until I found the trumpet teacher’s room. He explained to me that most people’s lips aren’t developed enough to make a sound from a trumpet until they’re at least ten years old and was quite impressed that I could. I loved the idea that not everyone could pick up a trumpet and be able to play it. I felt like it gave me a purpose.

My brother and I used to play together a lot. He taught me how to jam and improvise and he even organised a lesson with a friend of his who was in a band that I was a huge fan of. The condition of the lesson was I had to practise for at least half an hour every day for thirty days straight. I kept a journal to record my practising and eventually I got my lesson.

I went on to teach myself guitar many years after my mum had tried to convince me to. Mostly because I was writing my own music and wanted an instrument I could play to accompany my singing. My eldest brother was a huge inspiration for me in my music writing. He supported me and helped me and I looked up to him because of his musical skills and talents. He was the one person who gave my music dedicated time and appreciation.

One of my first very strong musical influences was Missy Higgins. The fact her look wasn’t necessarily traditionally feminine was huge for me. I have a strong connection to her music and am a big fan. A lot of the music I have written has been influenced by her style of songwriting.

Another musical influence was P!nk. She was my first exposure to a woman who was comfortable with her own masculinity: powerful and outspoken. Her music helped me get through a lot of hard times. I saw myself in her – saw who I wanted to be – and I developed a deep connection with her lyrics. Her early music addressed the invisibility I felt as a child and showed me that my feelings and opinions were not invalid because of my age. I felt like she understood and heard me and gave me a voice. Her music was a comfort, particularly through the time when my parents were having issues. I am grateful for the effect she had on my life. She taught me to be my own hero, to save myself and that if I want a role model, I may have to be my own.

More recently, the body of work created by Peaches has inspired me. She is a powerhouse of knowledge of gender and sexuality.

When I was younger I had a few aspirations for my future. I wanted my first job to be as a lolly-maker in a lolly shop. I had plans to be an eccentric scientist, veterinarian or astronaut. When I realised these may not be the most realistic of dreams, I decided I wanted to be a famous actor. After my mum finished work at my previous school, she took over a drama school from her friend and ran after-school drama classes. My mum and I are both quite theatrical, and I felt comfortable expressing myself through acting.

I went on to compete in drama competitions. I put pressure on my mum to find me an agent. She was never that passionate about it, so eventually I took things into my own hands. I found an agent. He told me he had to take headshots of me in order to get me jobs. He was located in Queensland and luckily we had a holiday house there, which was my great-grandmother’s old apartment. When we went up for a holiday, I got my headshots. I found the whole experience unbearable. I had no idea how to “model”, and at the end of the shoot he said to me, “I’m not going to tell you to lose weight, but I’ll tell you not to gain any more.” Thank you for contributing to my lifelong battle with body negativity!

Nevo, approximately six years old (2002)

Chapter 3: Misogyny For Beginners

Naturally, as young girls in a patriarchal society, my group of friends experienced misogyny. It was everywhere: in the media, at school, in our day-to-day lives. Unfortunately, misogyny is one of those things that shows up constantly. Don’t worry, if it doesn’t come from others, it’ll be so ingrained in your own view of the world your internalised misogyny will take over for any misogyny you’re missing out on, as if there’s some patriarchal quota.

There was an atmosphere all of us felt at school, of having to overcompensate as females in order to be addressed in the same way as the male students. Leila told me she felt she always had to be louder, pretend to be sure of herself, even when she wasn’t, to be taken more seriously. We would both get angry when teachers asked boys to help them lift things, when between Leila and myself,

we were stronger than all of them put together. There were always boys who had crushes on Shannon, announcing it and subsequently expecting things from her. Teachers made inappropriate comments about our appearances. Leila recalls being told by the art teacher (in relation to her arm hair) that her arms made her look like a monkey. One teacher pointed out my chubbiness often and made comments constantly about my unkempt, curly hair. It resulted in a lot of insecurity.

Leila developed the fastest of our group and was often victim to harassment on the street – badgering from men and catcalling. For a long time I blamed her. We all did. In a lot of ways, she was the girl I never was. She was confident, body positive, sex positive, deeply intelligent and articulate. She didn’t care about others’ impressions of her. I was constantly embarrassed by her eccentricity and lack of care. I realise now it was less embarrassment and more envy. The internalised misogyny I held closely to myself was often projected on to Leila. I felt she exaggerated her period pains to get attention and I had little sympathy for her when men would gawk and stare. I figured she had brought it on herself.

When she would come to us, distressed about a comment made on the street, or someone physically harassing her, I told her she shouldn’t have dressed the way she did. She shouldn’t have invited the comments. What did she expect when she had such large breasts? It was the price she had to pay. Anyway, she liked the attention, what was she complaining about? I wished men would look at me that way. I believed all of this, until one particular encounter. Leila was walking home from the train station one day. She was wearing her school dress, so was clearly under-age. A forty-year-old man was staring at her. She felt uneasy and looked away from him, and then he yelled out, “Nice tits.” She was probably eleven years old. That was the moment I knew it wasn’t her fault; she had done absolutely nothing. She was only trying to get home.

Growing up in a society that teaches women we are only as valuable as our appearance leaves many of us desperately needing validation. I didn’t feel valuable because men didn’t toot and catcall me. That’s how deeply misogyny was ingrained in me. I found myself wanting to be objectified in order to feel attractive. This is what I was shown day in and day out – through the media, parents, family, friends. At school I was policed on how short my dress was, taught not to go out on the street late at night, taught how not to be sexually assaulted. Very rarely have I heard that conversation conducted with my male friends. Very rarely are they taught how not to sexually assault, how to value women for more than the length of their legs, how not to blame women for being distracting by merely having flesh. Taught how to take responsibility for their own actions and thoughts and desires. Not all men sexually harass, but all men need to be taught not to.

I’m going to talk about periods. I don’t care if it causes you discomfort because I can guarantee that it’s a lot less uncomfortable than actually having a period.

Unlike a lot of trans people – or at least the ones I have spoken to – my period was not a distressing, traumatising or even upsetting experience. It was an inconvenience and one that I embraced. To be honest, sometimes I even miss it. My girlfriends and I had a tradition that after each person in the group’s first period, we would have a little period party and give each other gifts. It was fantastic. Truly counter to what we were mostly taught about periods, which was that they were unsanitary, dirty and a taboo topic for conversation. Certainly nothing to be celebrated. Sanitary item advertisements very rarely even mention the word “period”. The portrayal of women with their period is women who don’t seem to have their period; happily frolicking around town in white pants without fear. I don’t know about you but I am incapable of wearing white pants regardless of whatever sanitary item I may be using. A tampon does not protect me from myself, a notorious food dropper.

In case you haven’t noticed, these ads are lies. There is nothing about a period that is white. Periods are red. They’re bloody. They’re messy. They leave stains and they leak and they make themselves known. When having their period, people don’t appear happy and calm as they do in advertisements. They’re in a war zone. They’re probably angry and in pain. Their body is bleeding out and repairing itself and preparing for a new month. That is hardcore!

For me, my period was a symbol of strength and mindfulness. It was a time of the month where I had only to focus on my needs, both physical and mental. And the fact that we often dismiss people’s emotions when they have their period is ridiculous. If anything we should validate their feelings even more, because chances are they have a much heightened awareness of what their needs are at that time. I would also like to point out that there are lots of women who do not have a period, and it certainly does not make them any less of a woman. We have associated periods with womanhood, but this is an incorrect association. There are people of all genders that have periods, and people of all genders that do not.

Leila was the first of our group to get her period. We were all confused, awkward and secretly jealous. We celebrated her period, though she says she felt alone at the time. She was confused that her body was developing faster than her best friends. When Leila got her first bra, I tried desperately to persuade my mum to get me one too. She explained I didn’t need one as my chest hadn’t developed enough. I tried to convince her by jumping around the house to show how much my breasts would bounce. They didn’t, but she let me get a crop top as a compromise.

At the end of Year Five, my family and I went on a trip to Israel. For the most part it was fantastic. I remember long car drives, beautiful Hebrew music, practising my own Hebrew, my eldest brother writing flashcards (mostly so he could learn Hebrew profanities), unbelievable food and views, and getting to meet my Israeli family.

One night, my parents were having an argument about something and I decided I would try to mediate. I sat with them, asking each for their perspective and attempting to sort through their issues. Not the typical responsibility of a ten year old. It resulted in a huge blow-up with my parents screaming at each other, then me, and then at each other again. Eventually, I ran out of the room in tears. I went next door to where my siblings had congregated.

I didn’t have a close relationship with my siblings at that point. They were all at least ten years older than me and at very different stages of life. They comforted me and told me if my parents got a divorce they would support me and be there for me. They told me about my father’s divorce from their mother and how they coped. It was the first time I felt genuinely close to them and, to be honest, loved by them. They made it clear I would always be part of the family – something I didn’t always feel growing up. I was certain my parents would get a divorce, but they stayed together for another three years.

Making the decision about which high school to go to was a daunting one. I sat for scholarships at various schools, but I was afraid to approach the private Jewish school world after the experience I had in primary school.

I would be separated from the people who had become my safe place. Shannon would be attending another Jewish school, different to the one I was looking at, and Leila was moving to a girl’s school. Siobhan was coming to my new school with me, which was fantastic, but our relationship individually was not yet strong and we didn’t feel like we could turn to each other for support. I was worried I wouldn’t fit in and would be bullied again. I was also worried I wouldn’t be able to control my anger again and would revert to being a bully.

I eventually found a few people I could get along with – all girls – and we developed a friendship. The school I went to was small: around sixty kids per year level and the social dynamics were not easily changed. But I found those I felt comfortable with and we got along quite well.

For my first school camp at my new Jewish high school, I was placed in a cabin with a group of popular girls that I was intimidated by and, up until then, had stayed away from. There were many underlying passive aggressions that could easily be dismissed as being paranoid or misreading the situation. This is ho

w mean people function for the most part. The meanness is so subtle that you begin to question yourself.

On the first day I was in the cabin, a spider appeared and everyone ran out screaming. I didn’t understand what was going on, and just wandered out. I was looked at with such judgement that by the next day, when there was another spider in the cabin, I was the first one running out and screaming. I realised I would never fit in with this group of people if I presented in a masculine way. Once again, I tried to conform to femininity to make friends.

School swimming was really difficult for me. In my early years of school, we were made to get changed in the swimming pool area in front of everyone. I was always self-conscious. I loathed taking my clothes off in front of the other kids. I was able to blend in with the other boys until it came to taking my clothes off. It was in those moments that I was aware of how different I was to the other girls. I hated that I had to wear a one-piece bathing suit, I just wanted to be like the other boys. This experience became one of the first ingredients in a recipe for lifelong dysphoria.

The first swimming lesson we had in high school, I was nervous. I felt more at ease blending in with the girls than I had before, and so I wasn’t as paranoid about getting changed. I also had the luxury of changing in a cubicle. But as I sat in my one-piece on the benches, waiting to get into the pool, the girl next to me looked at my legs and said, “Wow, how are you not wearing board shorts? I get so insecure about my legs, I can’t deal with my thighs being exposed.” She was admiring my confidence and I think identifying that we had similar body types. She was extending some loving solidarity for a fellow fat girl in bathers. However, at this time, I saw being fat as a bad thing and rejected any idea that I could be fat. To be compared with her and admired for my confidence was an insult to me. I was deeply offended and became aware again of my size and weight. For every swimming lesson from then on, I wore shorts.

Finding Nevo

Finding Nevo